Extended wildfire season in the American West, deadly floods in Europe, sea level rise threatening island nations, severe heat waves. In every corner of the globe, we are witnessing firsthand the impacts of climate change on humans, wildlife, and ecosystems. In this issue of our Community Wellness newsletter, we explore Buddhist perspectives on the climate crisis. How can Buddhist teachings help us understand our relationship with the natural world? How have modern environmentalists been inspired by Buddhism to enact social and political change and vice versa?

We are all familiar with the causes of climate change in the modern era. Industrialization, the drive for economic growth, materialism, technological advancements, and population growth have all contributed to a global rise in temperatures. These factors have led to species extinction, resource depletion, destruction of ecological habitats, and widespread pollution.

Since the 1970s, religious leaders of many faiths from around the world have joined the chorus of voices calling for humans to take action to arrest the effects of climate change. Buddhists from various lineages--academics, lay people and ordained religious leaders--in Asia and the West have been at the forefront of this emerging field at the intersection of religion and ecology.

Green Buddhism, or ecodharma as it is sometimes called, has as many definitions as there are practitioners. Kritee (Kanko), a climate scientist and Zen priest, views ecodharma “as an holistic framework – a framework to build a unified movement towards justice, equality, health and joy where deep ecology meets strategic activism, deep love and sense of inter-connection with the past, present and future worlds meets our words and collective action, and our emotional, intellectual and spiritual energies converge.” The movement arose as part of the broader activities of socially engaged Buddhists who sought to apply Buddhist ethics to the social, political, and environmental issues facing humanity in the modern era.

Below we highlight a selection of examples of ecodharma activism from around the world.

Vietnamese monk and spiritual leader Thich Nhat Hanh, one of the pioneers of the engaged Buddhism movement, has spoken with clarity about the need for a new global ethic to protect the earth. In The World We Have published in 2008, he encourages people to follow the Buddha’s Five Mindfulness Trainings. In doing so, “you become a bodhisattva helping to create harmony, protect the environment, safeguard peace, and cultivate brotherhood and sisterhood. Not only do you safeguard the beauties of your own culture, but those of other cultures as well, and all the beauties on Earth” (quoted from an excerpt from the book, published in Lions Roar).

Although the prominent figures in the Japanese environmental movement have more often been associated with Shintoism, Buddhist leaders have engaged in various aspects of activism, from habitat protection to protesting toxic waste dumping. Masanobu Fukuoka, an agriculturist turned farmer, revolutionized farming with his One Straw Revolution, inspiring thousands of back-to-the-landers and permaculture advocates across the world. His philosophy of do-nothing farming is rooted in the heart of Zen teachings.

In Taiwan, a socially engaged “humanistic” version of Chan Buddhism developed out of the teachings of Venerable Taixu (1890-1947). This type of Buddhism flourished with the founding of institutions like Fo Guang Shan Temple, which was established by Venerable Master Hsing Yun in 1967 and now supports more than 200 branches around the world. In addition to education, culture, and social services, humanistic Buddhist organizations often carry out environmental protection. In their article “Taiwan’s Socially Engaged Buddhist Groups,” David Schak and Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao write of the various groups, “Fu-chih, Ling Jiou Shan, Tzu Chi and Fo Guang Shan directly contribute to environmental protection. Fu-chih does so through its organic agriculture programmes and Ling Jiou Shan through seaside clean-ups and conferences. Tzu Chi and Fo Guang Shan have very extensive litter collection and recycling programmes.”

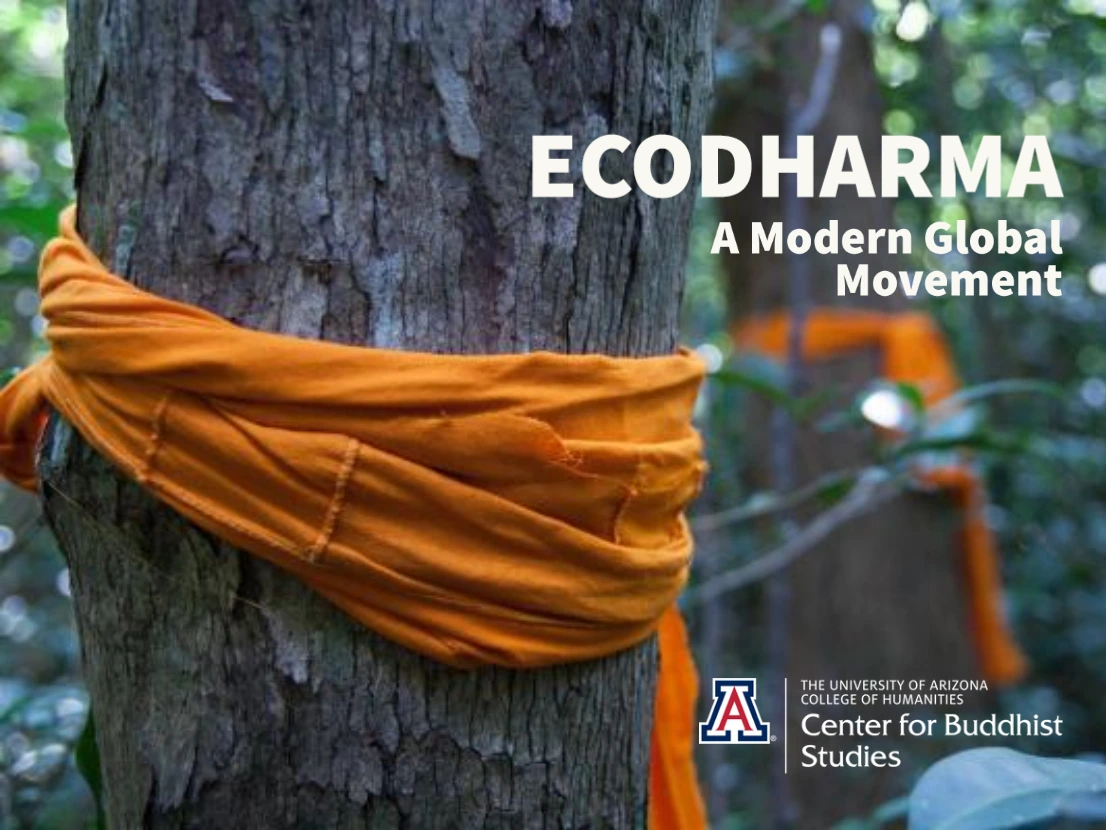

Famously in Thailand, farmers and monks from the Thai Forest tradition placed orange robes on trees and “ordained” them to raise awareness of the need to protect old growth in tropical forests. The revered monk Buddhadāsa Bhikku, founder of the Suan Mokkh temple and retreat center, taught a reformist version of Theravada Buddhism and explored social and ecological issues from a Buddhist perspective. His Theory of Dhammic Socialism is based on nature in a state of balance, with all beings producing and consuming only according to their needs.

“If we were to use the earth’s resources according to the laws of Nature and within its limits, we would not need to use as much as we do now…Nowadays, however, we are squandering the earth’s minerals so destructively that before long they will be gone... If we were to use them as we should, according to the laws of Nature, there would always be an abundant supply” (Buddhadāsa, “Democratic Socialism,” p. 51, cited here).

Sulak Sivaraksa, a Thai professor, writer and social activist, was a forceful critic of consumerism and unfettered development, and revered for encouraging “spiritual friendship” among people from different countries and backgrounds. In 1989, he helped to establish the influential International Network of Engaged Buddhists, along with Thich Nhat Hanh and His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

His Holiness the Karmapa, head of the Karma Kagyu School of Tibetan Buddhism, founded the Khoryug movement in 2009, resulting in the greening of many monasteries in the Himalayan region. According to their website, “Khoryug member institutions have planted over 100,000 tree saplings in the past ten years. All Khoryug institutions are vegetarian, sort garbage and recycle, and carry out community clean up exercises. More than half of them have installed solar, carry out organic farming and compost their food waste.”

In 2011, His Holiness the Dalai Lama convened a dialogue in Dharamsala, India, with leading thinkers on climate change. Organized by the Mind and Life Institute, the week-long meeting resulted in the 2018 publication of the book Ecology, Ethics, and Interdependence. One presenter was Dekila Chungyalpa, a South Asian environmental activist with the World Wildlife Foundation. In 2009, she started the initiative Sacred Earth: Faiths for Conservation to train religious leaders in the fundamentals of environmental work. She now directs the Loka Initiative at the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin and serves as the environmental adviser for His Holiness the Karmapa.

Tibetan scholar and teacher Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a leading figure in the dissemination of Tibetan Buddhism in the West, established Naropa University as a Buddhist-inspired ecumenical institution in Colorado in 1974. Known for its emphasis upon contemplative education and expressive arts, Naropa now offers a Master’s degree in Ecopsychology.

Academics working on Buddhism and ecology in America were inspired by thinkers like Thomas Berry, a cultural historian by training and an influential voice in the religion and ecology movement. In his 1999 classic The Great Work, he stated that “Perhaps the most valuable heritage we can provide for future generations is some sense of the Great Work that is before them of moving the human project from its devastating exploitation to a benign presence. We need to give them some indication of how the next generation can fulfill this work in an effective manner.”

Berry’s former students Mary Evelyn Tucker and her husband John Grim have continued his work as co-directors of the Forum on Religion and Ecology, now at Yale University. They have created a multimedia project Journey of the Universe, a film, book, and series of courses inspired by Berry’s call for a “new story” to inspire wonder, awe, and an appreciation for the interdependence of all life.

Tucker and Grim organized a series of conferences that took place at Harvard University between 1996 and 1998 and resulted in the publication of a series on Religions of the World and Ecology, which included Buddhism and Ecology, edited by Mary Evelyn Tucker and Duncan Ryūken Williams.

Also influential in the ecodharma movement in the West were those associated with deep ecology, a philosophy of environmentalism that values all life forms regardless of their utility to humans. Joanna Macy, one of the grandmothers of American Green Buddhism, has made a profound mark with her many workshops and books, the most famous of which is The Work that Reconnects. Through rituals like the Council of Beings, developed by Joanna Macy and John Seed, participants place themselves in the position of another species, speaking on behalf of that species and delivering a visceral experience of the interdependence of all beings. Stephanie Kaza, professor emerita of Environmental Studies at the University of Vermont and author of Conversations with Trees, combines an academic pedigree in biology with Soto Zen Buddhist training. Through personal and intimate writings on the intersection of religion and ecology and involvement in the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, she has become a leading figure in the American Green Buddhism movement.

Other key figures in the American scene include Zen teacher and Buddhist Peace Fellowship co-founder Robert Aitken, John Daido Loori of the Zen Mountain Monastery in upstate New York, and Gary Snyder, poet, environmental activist and author of Turtle Island. David Loy, an American professor, Zen teacher, and author of Ecodharma, remains active today as a lecturer and teacher. He is one of the founding members of the Rocky Mountain Ecodharma Center near Boulder, Colorado.

Criticisms and Concerns

Lewis Lancaster warned that collective cultural perceptions of Western academics and activists could lead us to selectively read Buddhist history and practice, and cherry pick what fits with pre-existing Western notions. For example, modern narratives about Sakyamuni as a wandering ascetic whose enlightenment took place under a Bodhi tree cloud the fact that “he nonetheless taught and lived in the precincts of the growing urban world of his time,” and received financial contributions from kings and merchants (“Buddhism and Ecology: Collective Cultural Perceptions,” in Buddhism and Ecology, p. 12). Others argue that Buddhism is not a “nature religion” such as paganism or many Indigenous spiritual traditions, and its core tenets still revolve around human suffering and its alleviation. Some critics, especially those who study the Pali canon and Theravadan traditions, argue that the passionate, sometimes angry rhetoric and actions of social activists falls out of line with dhamma teachings on detachment (Allan Badiner explores these objections in this Tricycle article).

The ongoing debate about ecodharma, and the plethora of books, articles, retreats, and trainings on the topic, is a testament to its influence in Engaged Buddhist circles. With interest from academics, lay people, and religious leaders in many lineages and countries, the movement seems destined to remain relevant and evolving as the climate crisis intensifies.